Erarta Museum of Contemporary Art presented an exhibition of collages by the Dutch artist Tamara Stoffers offering a new take on the Soviet aesthetics

-

A surreal re-imagining of the visual legacy of the USSR

-

An aesthetic utopia recreated by the Netherlands-based artist born after the demise of the Soviet Union

-

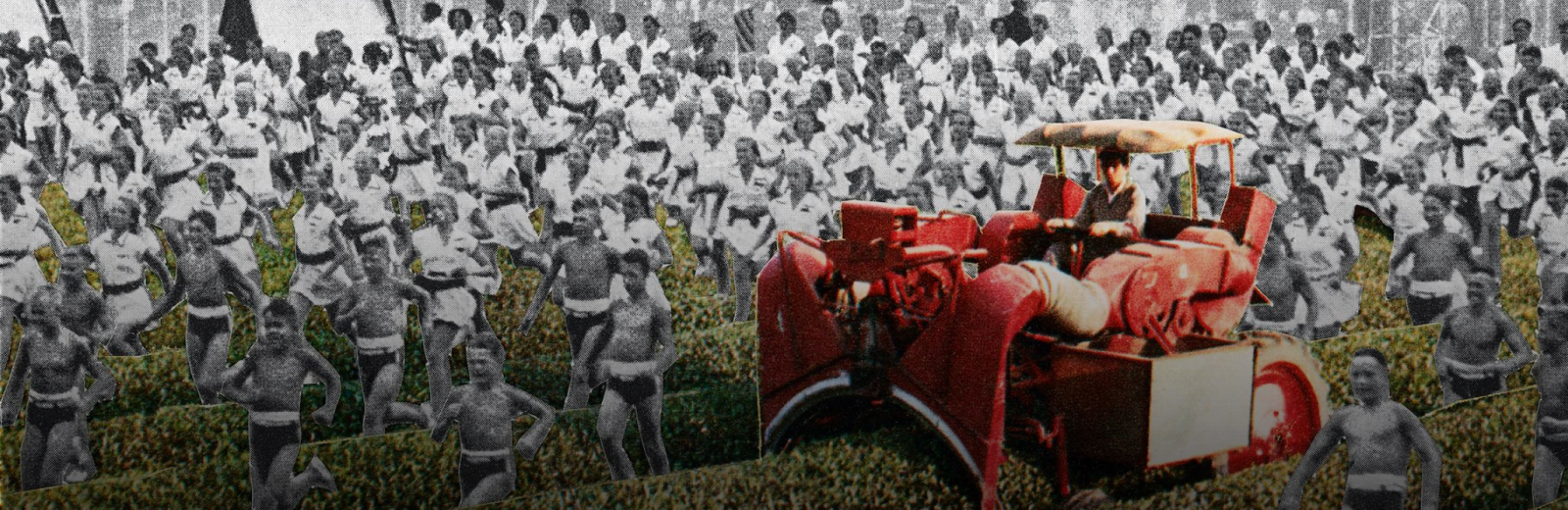

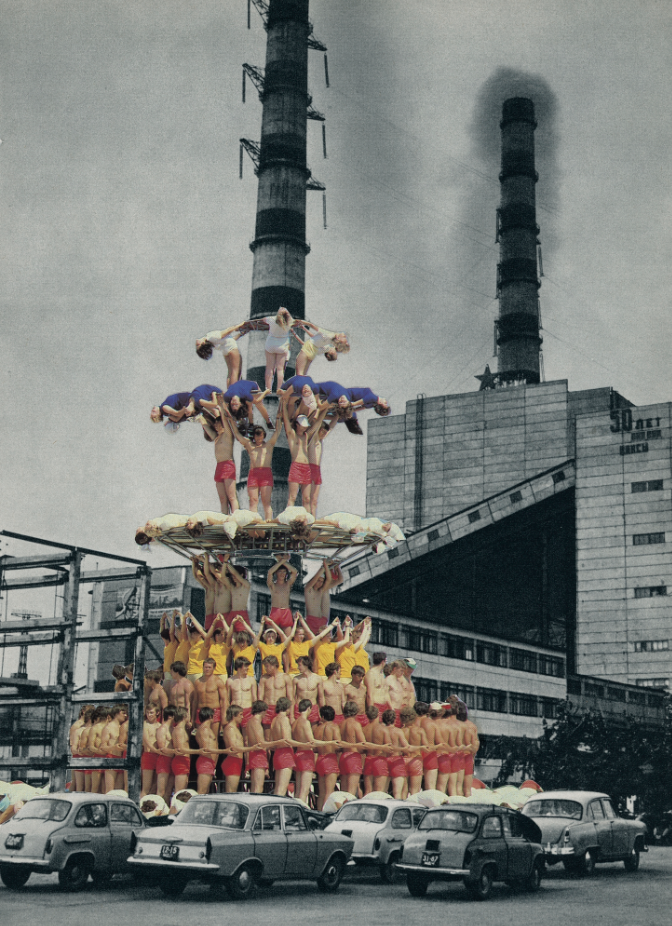

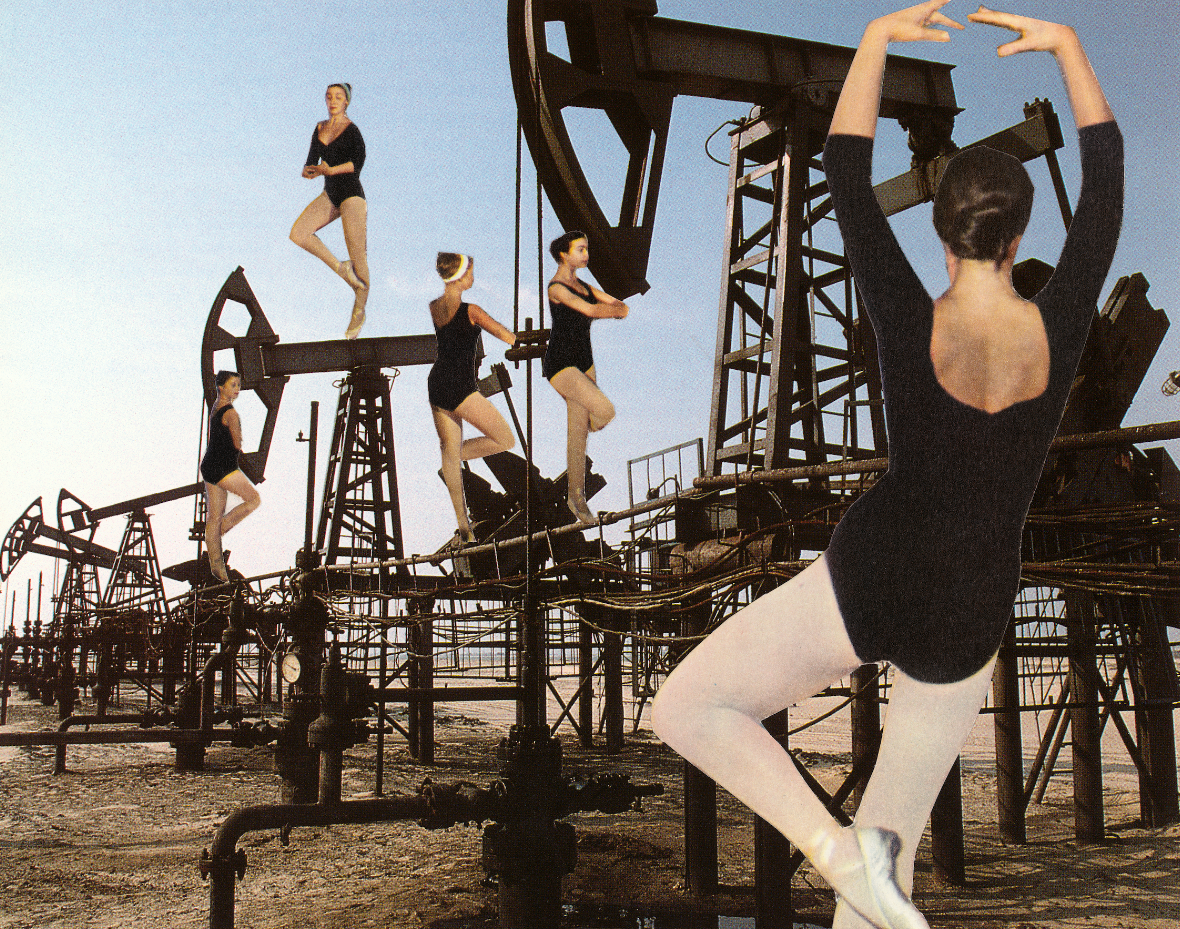

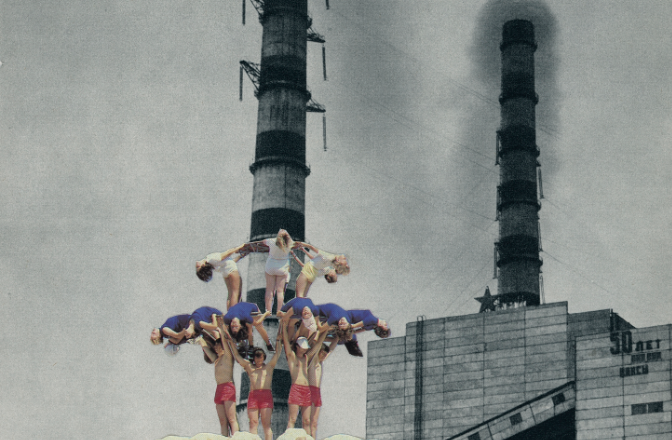

Vivid imagery marrying Soviet visual propaganda and the traditional artistic medium of collage

Although the Dutch artist Tamara Stoffers resides and works in the Netherlands, not very long ago she aspired to enrol at one of the famously conservative major Russian art schools. While preparing for her entrance exams, she had discovered the legacy of Soviet visual culture and was fascinated with it to the point of having learnt the Russian language to better understand it. This twist of the plot is hardly surprising: it is quite likely that the very reason why the Soviet aesthetic sensibility ended up to be so enduring lies in the Russian tradition of art education which for three solid centuries has been focusing on teaching the skills and craftsmanship based on the classical beauty ideals.

For Tamara Stoffers, who was in awe of the old masters’ paintings and had not visited Russia until 2017, the ‘Soviet world’ became a kind of aesthetic utopia. Browsing through second-hand bookshops and flea markets, the artist would come across glitzy books and postcards published for foreign readers in the times of the so-called ‘developed socialism.’ The enchanting atmosphere of half-empty streets lined with spanking new International Style buildings and colourful babushka portraits enticed her to embark on a lengthy surreal journey. Armed with a pair of scissors and some glue, Tamara Stoffers took off into the Soviet cosmos straight from her little room in a Dutch residential community in which she recreated the interior of a typical communal apartment as she imagined it – much to the delight of her four neighbours.

It is a known fact that in the Soviet Union the sphere of visual communications – in other terms, propaganda – was a matter of state importance. The country’s best poets were busy rhyming promotional slogans, while its best photographers and designers decorated national pavilions at world fairs. The ‘export-worthy’ coffee table books and magazines of the 1960s and 70s project a very distinctive atmosphere. The Soviet printing industry was a dream factory in its own right where a reportage shot of some event could easily re-enact the Laocoön Group. Rather than capturing life as it is, these photographs present it the way it should be: people are concentrated at work and happy at leisure, cities are green and clean, and collective farmer hostels are cosy and inviting.

Virtually any contemporary lifestyle magazine contains a feature inspired by the Russian avant-garde or conventionalised ‘totalitarian aesthetic’ – whatever the latter is supposed to mean. Roughly two decades ago, Germany and other countries of the Eastern Bloc were swept by a phenomenon known as Ostalgie: boys and girls too young to have lived in the German Democratic Republic began rummaging for old jackets in their families’ closets and reverently collecting mass-produced items which, according to their parents, used to be difficult to obtain. Soviet design exhibitions are still invariably popular, just as the retro style, bound to be forever nurtured by the grandchildren’s interest in the lives of their grandparents. The art of Tamara Stoffers is a striking example of such unusual aestheticising of the Soviet past. The artist is building a surreal world through the rather traditional medium of collage. Interestingly enough, similar visual experiments can also be found on the pages of Sovetskoe Foto magazine, as well as in the creations of the famous Soviet architect and artist El Lissitzky.

Tamara Stoffers (b. 1996) is a Dutch visual artist who expresses herself through both written and visual means. Since her graduation from the art academy in Groningen in 2017, she has built a consistent and ongoing series of photographical work. This is a body of analogue collages, composed from images originating from Soviet publications. She sees her artistic practice as a mode of research into the visual language of the USSR. To better be able to study primary sources of information, she learnt the Russian language and completed the pre-master program of East European Studies at the University of Amsterdam in 2023.

Supported by: